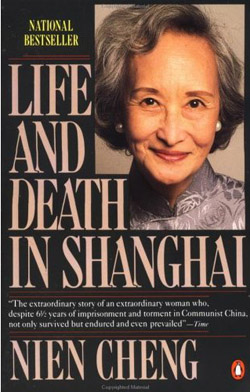

“The past is forever with me and I remember it all now,” starts Nien Cheng’s gripping account of her life during China’s Cultural Revolution. Though published in 1987, “Life and Death in Shanghai” is still as potent a read as ever. In it, Cheng recounts how the Red Guards ransacked her house in Shanghai in 1966 and put her in prison for 6½ years in solitary confinement for being a “class enemy and running dog of the imperialists.” Widowed at the time and living with her daughter, Cheng worked at Shell Oil till the Maoists closed its Shanghai office. In the book, Cheng describes the harsh interrogations and tactics used in prison in attempts to make her confess (falsely) to being a “spy.” But despite torture and deteriorating health, she never does. She remains vigilant in refuting the Maoist revolutionaries’ accusations and survives till her release, only to find out after, tragically, that revolutionaries had killed her daughter. She forges a plan to leave China, which she does in 1980 at the age of 65 with just one suitcase and $20, eventually settling in Washington, D.C., where she has lived since 1983.

Her book is a compelling survivor’s memoir that includes a fair share of informative historical and political context about the Cultural Revolution. I found it an extraordinary story of a courageous woman, who I had the great fortune to meet for tea early in April 2009. She greeted me at the lobby of her condo building and appeared quite younger than her 94 years. She was very gracious, warmhearted, and open.

We made the trek to her floor and she seemed fine, though slowed she said by the arthritis where the Communists had beaten her. There for four hours, she spoke of her life, the Communist government, the book and subjects that came to her, and I mainly listened not wanting to move or interrupt. She was quite amazing, her mind and memory were sharp and I realized, as her book’s first line states, that indeed she “remembers it all.”

She made references to life during the Sino-Japanese War (1937-1941); listening to Winston Churchill on the radio when she attended London’s School of Economics as the first Chinese woman; living in Australia as a Chinese diplomat’s wife during the attack on Pearl Harbor; surviving life under Mao; and attending a White House State Dinner at the Reagans’ request after her book was published in 1987.

Indeed, hers is a remarkable 20th-century life. And yet she talked about it very modestly, and chalked up the book’s success solely to timing. When it was published she said there wasn’t much about the Cultural Revolution; it was still not widely written about. Her book she said took about two years to write upon her arrival in D.C. in 1983, which she did on a manual typewriter, and a third of which she left on the cutting-room floor. I asked her why she hadn’t written another book after her first one had become a bestseller, and she said back then she still feared Chinese reprisal. But she laughed when she said her book had sold well for a while in China before the Communists found out and banned it. She had been back to Hong Kong but said she would never go back to mainland China.

“I can forgive them for imprisoning me,” she said, “but I can’t forgive them for murdering my daughter. … I never found out who killed her, the Communists just wanted to cover it up.” The loss of her daughter is with her everyday, and she feels guilty, she says, for having been the one to have lived. And yet, what she’s left readers is an invaluable life and look at Maoist China.

You were so lucky to meet her. What an honor. So glad you included you included it with your review.

Keep up the good work!

What an extraordinary woman, thanks for sharing her story.

What an extraordinary woman and how wonderful that you had a chance to meet and speak with her, something I am sure you’ll always remember.